The Varsity line: from Railway Mania to Beeching's Axe

January 28, 2026

A train to Oxford at Bedford St Johns station before the Varsity line's closure

East West Rail (EWR) is an Oxford–Cambridge railway route, currently under construction, serving Bicester, Milton Keynes, Bedford and Tempsford (a new town development). It’s being delivered in stages:

- Upgrading Oxford–Bicester

- Reinstating Bicester–Bletchley

- Refurbishing Bletchley–Bedford

- Building a new route towards Cambridge

With attempts over the last twenty years to get it reopened, it’s a project I’ve had my eyes on for a while, partly because it promises to fix a fundamental flaw: Britain’s rail network evolved radially around London, leaving regional centres poorly connected to each other.

This wasn’t an issue until the 1960s, much of the EWR alignment follows the old Oxford–Cambridge Varsity line, a Victorian-era cross-country route, stitched together from sections built by competing railway companies. It linked market towns, two of the UK’s leading university cities, and provided a strategic alternative to London for certain flows. Passenger services over most of the line withdrew after 1967, leaving the Bletchley–Bedford section (today’s Marston Vale line) as the main survivor.

The closure came during the Beeching era where British Railways faced heavy losses and government policy treated the railway as a business that must pay its way, rather than public infrastructure where losses serve a social purpose. Like roads, schools, or hospitals, railways don’t need to be profitable to be valuable – they exist to serve communities, connect labour markets, and enable economic activity that wouldn’t otherwise occur. Beeching’s 1963 report quantified “uneconomic” mileage and stations, proposing radical pruning of the network to stem deficits. Something that may look rational on a spreadsheet, but…

The problem is that railways are not spreadsheets – they are networks. A line that looks weak in isolation can still be valuable as it feeds demand into stronger corridors, gives the system resilience, and shapes where people live and work. When these links are removed, costs are reduced, but this also changes behaviour, often pushing trips onto roads and discouraging rail travel altogether.

So why was the Varsity line closed, what did Beeching get right (and very much wrong) about “efficiency”, why is rebuilding an Oxford–Cambridge link justified now, and how can the economic benefits be maximised?

Spoiler: It’s not just nostalgia, it’s a response to a London-centric network, congested roads, lack of housing stock, and the economic logic of connecting regional clusters – including the often-overlooked first- and last-mile of journeys. EWR’s success hinges less on track-laying than on governance, operations, and access – areas where UK transport policy has historically failed.

History

Railway Mania

Britain is the birthplace of the modern railway. Whilst the Stockton & Darlington Railway opened in 1825, it was the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (the first inter-city line) in 1830 that demonstrated the transformative potential of passenger rail with scheduled services, reliable timetables, and the ability to move people and goods at unprecedented speeds. The success of this line ushered in a period known as “Railway Mania”. Investors and landowners rushed to fund new railways, fearing they’d miss out on the fortunes being made. Between 1844–1846 alone, 6,220 miles of railways were approved, almost dwarfing the 9,848 miles of today’s main line network. In essence, everyone wanted a railway regardless of profitability.

This boom in railway building wasn’t centrally planned. With hundreds of competing companies seeking profit and prestige, the result was a dense network with considerable redundancy. Different companies would build parallel routes to the same destinations, each seeking their share of traffic. This is why South London’s rail network remains poorly connected today – competing Victorian companies created a patchwork of dense lines that never integrated properly.

As the network matured, a hub-and-spoke pattern emerged with major trunk routes between cities (the ‘main lines’) and smaller branches serving towns and villages, feeding traffic to the network’s arteries. By the 1900s, the UK had one of the world’s densest railway networks.

Among these schemes was a line connecting two prestigious university cities: Oxford and Cambridge.

The Varsity line

Like EWR, the Varsity line was built in stages. The first section opened in 1846 between Bletchley to Bedford, built as a branch from the West Coast Main Line. Four years later, the Buckinghamshire Railway extended west to Oxford via Bicester and Winslow. The final piece, Bedford to Cambridge, completed in 1862. The result was a 77-mile cross-country route assembled by multiple companies over sixteen years (typical of Victorian railway expansion), opportunistic rather than planned, but ultimately forming a coherent east–west corridor. In 1868, a branch opened from Aylesbury to Verney Junction (west from Winslow), later incorporated into the Metropolitan Railway (now London Underground’s Metropolitan line).

The line served multiple purposes from the outset. Economically, it unlocked Cambridgeshire’s fertile agricultural region, moving grain, livestock, and produce to wider markets, whilst carrying coal, building materials, and manufactured goods from Oxford’s industries eastwards. The impact was immediate: coal prices in Bedford almost halved after the railway arrived, spurring industrial development like the Britannia Ironworks, which opened beside the tracks and river Great Ouse in 1859.

Passenger traffic included university staff and students travelling between Oxford and Cambridge. Academic collaboration existed even in the Victorian era, along with affluent travelers seeking an alternative to London routes. Strategically, the line provided network resilience, connecting to main lines at Bletchley (West Coast), Bedford (Midland), Sandy (Great Northern) and Cambridge (Great Eastern). For the market towns along the route – Bicester, Winslow, Bedford, Sandy, St Ives – the railway transformed local economies, linking rural areas to regional and national markets whilst carrying mail and parcels that kept communities connected.

The line’s decline began well before Beeching. By the late 1950s, falling revenue prompted British Railways to consider complete closure in 1959, though the introduction of diesel multiple units – substantially reduced operating costs – temporarily saved the route. However, the economics painted a foreboding picture: by 1963, income covered barely half of operating expenses. Car ownership was rising rapidly, buses competed on parallel roads, and agricultural mechanisation reduced freight traffic.

The Varsity Line, like hundreds of branch routes across Britain, had become vulnerable. When Beeching’s report arrived in 1963, initially recommending retention with minor cuts, British Railways pushed for full closure anyway. By December 1963, the line’s fate was sealed. But why had British Railways become so determined to close what had once been valuable infrastructure? The answer lies in a fundamental misunderstanding of how railways work.

Beeching’s cuts

By the early 1960s, British Railways faced an existential crisis. The nationalised network was losing £104 million annually in 1962 – roughly £2 billion in today’s terms – with losses running at £300,000 per day. The 1955 Modernisation Plan, which had promised profitability by 1962 through dieselisation and electrification, had clearly failed. At the same time, car ownership was exploding.

The M1 motorway, opened in 1959, symbolised a modern Britain that seemed to have no place for railways, let alone Victorian-era branch lines. British Railways solution was Dr Richard Beeching, a physicist and ICI technical director with no railway background, appointed Chairman of British Railways in 1961 on a salary that exceeded the Prime Minister’s.

Beeching’s solution

Beeching’s solution arrived in March 1963 with his report, “The Reshaping of British Railways”, grounded in hard data. The statistics were cataclysmic. One-third of the network’s route miles carried just 1% of passenger traffic.

On paper, closing 5,000 miles of uneconomic branch lines (30% of the network) and 2,363 stations (55% of all stations), concentrating resources on profitable trunk routes, and using buses to handle dispersed rural travel seemed like an obvious solution. The savings would fund modernisation of the core network. It was rational, data-driven thinking applied to a loss-making industry that was haemorrhaging money. Beeching himself was unapologetic. “I suppose I’ll always be looked upon as the axe man, but it was surgery, not mad chopping.”

His report treated railways as a collection of individual lines rather than an integrated network – a network where unprofitable branches fed traffic into the profitable trunk routes. A Winslow resident travelling to London would take the Varsity Line to Bletchley, then the West Coast Main Line to Euston. Close the Varsity Line, and you don’t just lose Winslow-to-Cambridge travel – you lose the Winslow passenger’s main line revenue too. This network effect doesn’t appear in Beeching’s accounting.

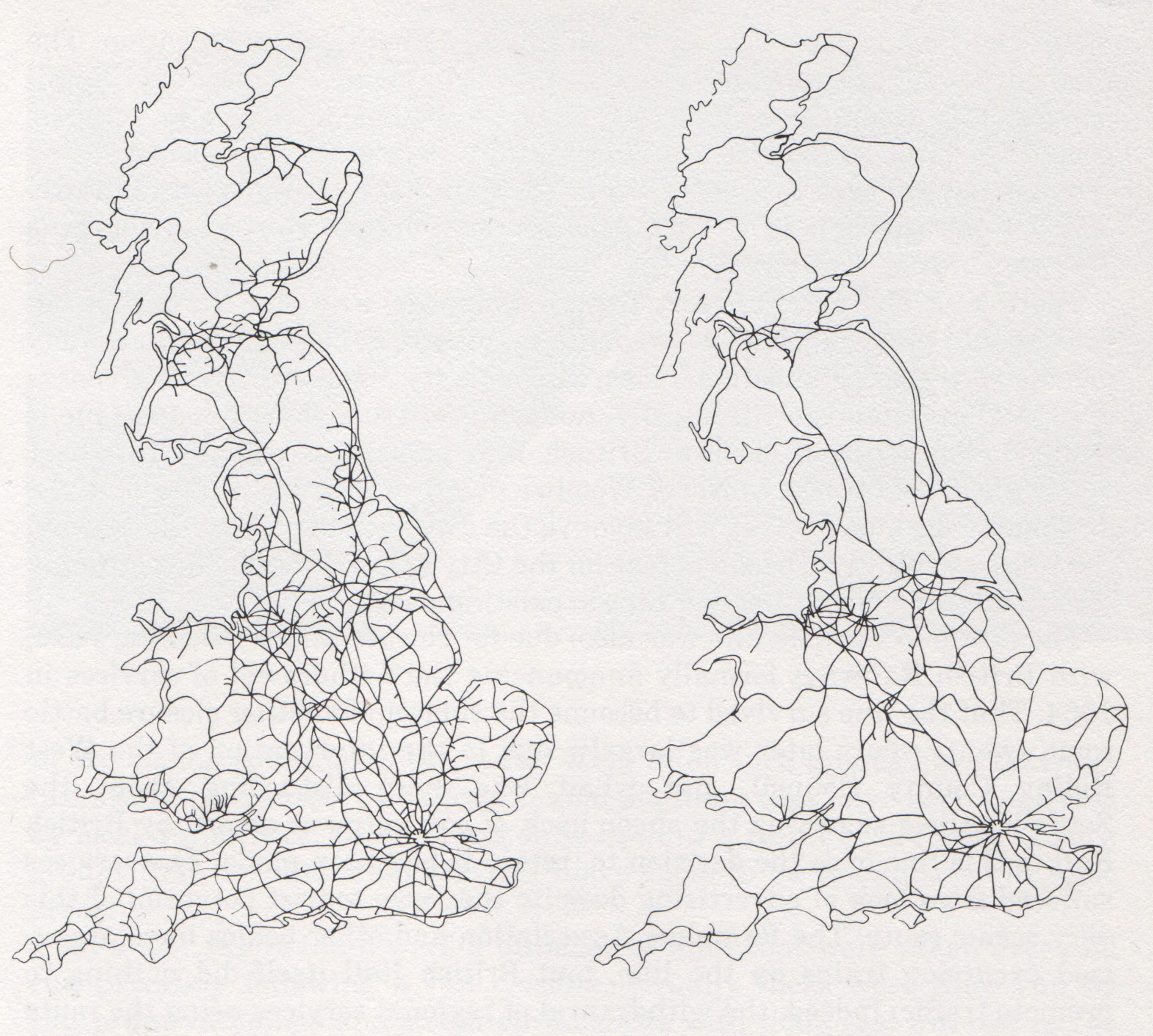

The railway network in 1963 (left) and 1984 (right), showing Beeching's effect

Was it really a solution?

Short answer: no, far from it actually…

Despite closing nearly a third of the network, Beeching achieved savings of only £30 million whilst losses plateaued. Bus replacement schemes failed just as badly. Most services lasted less than two years before being withdrawn due to lack of patronage, leaving communities with no public transport at all.

They were slower than trains and stopped at former station sites rather than population centres, adding more friction to rail travel. Those who had access to cars would be incentivised to drive the whole journey than drive to the nearest station and take the train from there, so car dependency accelerated, which is exactly what Beeching had claimed to be responding to. Contrary to his belief, rationalisation contributed to a fall in main line railway usage.

Towns that lost their railways saw economic decline. The spreadsheet analysis was mathematically correct but systemically blind. Beeching had brought a physicist’s rigour to the problem but lacked the railway experience to understand what the numbers actually meant. By 1968, it became clear that closures weren’t fixing the deficit and never would.

Marston Vale line – Bletchley to Bedford

Through local opposition to bus replacement, the Marston Vale line emerged as the sole survivor of the Varsity line’s 1967 closure, though heavily downgraded. Stations lost their goods and parcels facilities and became unstaffed halts. Line closure was proposed again in 1972, prompting the formation of the Bedford Railway User’s Association.

With freight traffic from the brickworks at Stewartby (soon to be the site of Universal Studios), the recently completed new town of Milton Keynes contributing passengers, and strong local support led by the Rail Users’ Association, the Marston Vale line escaped closure once more.

Yet survival came at a cost. The 16-mile route retained double track along most sections but operated with basic signalling and minimal investment. Journey times of around 45 minutes made rail uncompetitive with the A421 by car, roughly 25 minutes off-peak. Service frequency remained poor: hourly at best through the 1970s–90s, gradually improving to roughly three trains per hour by the 2000s as Milton Keynes expanded.

Station infrastructure languished. Victorian platforms often located away from modern population centres, with minimal or non-existent parking and basic shelters at best. Passengers bought tickets on the train or in advance: these were unstaffed halts in all but name.

Current condition

The low-point came between 2019 and 2023 with the Class 230 ‘Vivarail’ experiment. The line’s constraints – platforms and level-crossings that would be fouled by trains longer than 40m, and no electrification – severely limited rolling stock options. Vivarail’s solution was to convert 1980s-era London Underground D stock into short main line diesel units, promising cost-effective capacity increases.

Instead, the trains suffered frequent breakdowns and maintenance complications, and service reliability collapsed. In December 2022, Vivarail entered administration and the experiment ended. The line operated replacement buses until early 2024, when dated but dependable Class 150 DMUs (cascaded from Northern) finally returned.

This surviving fragment demonstrates both why Beeching’s cuts failed and why comprehensive rebuilding is now justified. The line retained just enough utility to resist closure but never thrived. It proved that half-measures don’t work: keeping infrastructure alive without investing in it properly can push people away from it. If a railway is worth keeping, it needs investment which encourages its use, not compromises – EWR must be designed as a system.

What changed?

Sixty years after Beeching’s cuts, the circumstances that justified closure have reversed. What looked rational in the 1960s now appears as short-sighted destruction of valuable infrastructure.

The question isn’t why rebuild the Varsity line – it’s why it took sixty years to recognise the mistake. Four fundamental changes explain why East West Rail makes sense now when it didn’t during the Beeching era: the UK’s rail network topology remains inadequate for east-west travel, government policy has transformed from treating cars as the solution to recognising them as part of the problem, housing policy now explicitly links infrastructure to development, and political consensus has finally emerged after decades of failed attempts.

But understanding why East West Rail is needed is only the beginning. The Oxford-Cambridge corridor already hosts 19,000 companies employing 570,000+ people with £135 billion turnover: one of the UK’s most dynamic economic regions operating with lacklustre east-west connectivity. Part 2: Reconnecting the Supercluster examines the economic case for EWR, the delivery plan across three construction stages, and the controversies that threaten to undermine it – including the Marston Vale station consolidation plan and Universal Studios’ 8.5 million annual visitors who’ll depend on this infrastructure from 2031.